Rebecca Groebner MAc LAc

March 2015

OVERVIEW

71-year-old male presents with cough and severe shortness-of-breath, caused by emphysema. Initially, patient was stabilized during an emergency home visit. At patient’s request, palliative home care was provided. This type of care is necessary for anyone suffering from chronic illness, yet as doctors, we often don’t follow cases through to this point. How do we manage end-of-life care in rural Nepal?

71-year-old male presents with cough and severe shortness-of-breath, caused by emphysema. Initially, patient was stabilized during an emergency home visit. At patient’s request, palliative home care was provided. This type of care is necessary for anyone suffering from chronic illness, yet as doctors, we often don’t follow cases through to this point. How do we manage end-of-life care in rural Nepal?

Subjective

Patient presents with a chronic cough of 3 years duration and shortness-of-breath. Acute symptoms began 10 months ago when he presented with severe pain in the solar plexus area and inability to breath. He was diagnosed with allergies at the local health post, but allergy medications were not helpful. He was transported to a hospital and diagnosed with emphysema and a pneumothorax. 1 month ago, patient was hospitalized for a second time and sent home with an oxygen tank, which he requires for respiratory stability.

He is only able to breathe if he sits up straight or leans forward. Cold weather and fatigue make these symptoms worse. Warmth, warm water, sunshine, his nebulizer and black coffee make it easier for him to breathe. His cough is productive with white mucus that is sometimes tinged with blood.

In addition to this, the patient suffers from worsening anxiety, insomnia, sharp left-sided chest pain, weight loss, daily nosebleeds, constipation, loss of appetite and 1-sided edema in his right limbs causing leg pain when walking. His leg pain and sleeping are better when sitting in a cross-legged, seated position with pillows stacked behind him. All of these symptoms are made better by listening to the radio and visiting with friends and family, taking his mind off his pain.

Objective

Patient presents with a thin body. Clothes that once fit him are now baggy. His ribs, scapula and clavicle bones are easily visible. He becomes breathless with small movements. His facial color is blanched. Patient breathes out through pursed lips.

Patient has a score of 40 on the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS). Ambulation is low. He requires assistance from a caregiver for moving and elimination. He is unable to do any work. He can drink from a cup, but requires assistance to eat. Food intake is reduced, but water intake seems normal. He is often fully conscious or drowsy. He is rarely confused, unless his blood oxygen levels drop below 70%.

Patient has +1 pitting edema in the right hand and +4 pitting edema in the right foot. The leg feels room temperature on palpation. Dorsiflexion of the right foot causes pain and increases shortness of breath. Blood oxygen levels rise and fall, becoming more extreme over the course of our visits, with the lowest reading being at 63%. The pulse and respiration rates rise as the blood oxygen levels fall.

Lung exam shows increased expiration time with decreased lung sounds in the lower lobes. Lungs are clear to auscultation in the lower lobes. Soft to medium crackles and high-pitched wheezing on both inhalation and exhalation are present. An occasional pleural friction rub can be heard in the right middle lobe. Cardiac auscultation shows an irregular heart beat with an extended diastolic conclusion (S2). Both lung and heart sounds decrease over time.

The right radial pulse is weak and deep. The left is thin and deep. His tongue body is dusky with multiple cracks. The tongue coat is thick, dry, yellow and stringy. There is a +3 sublingual stasis.

Assessment

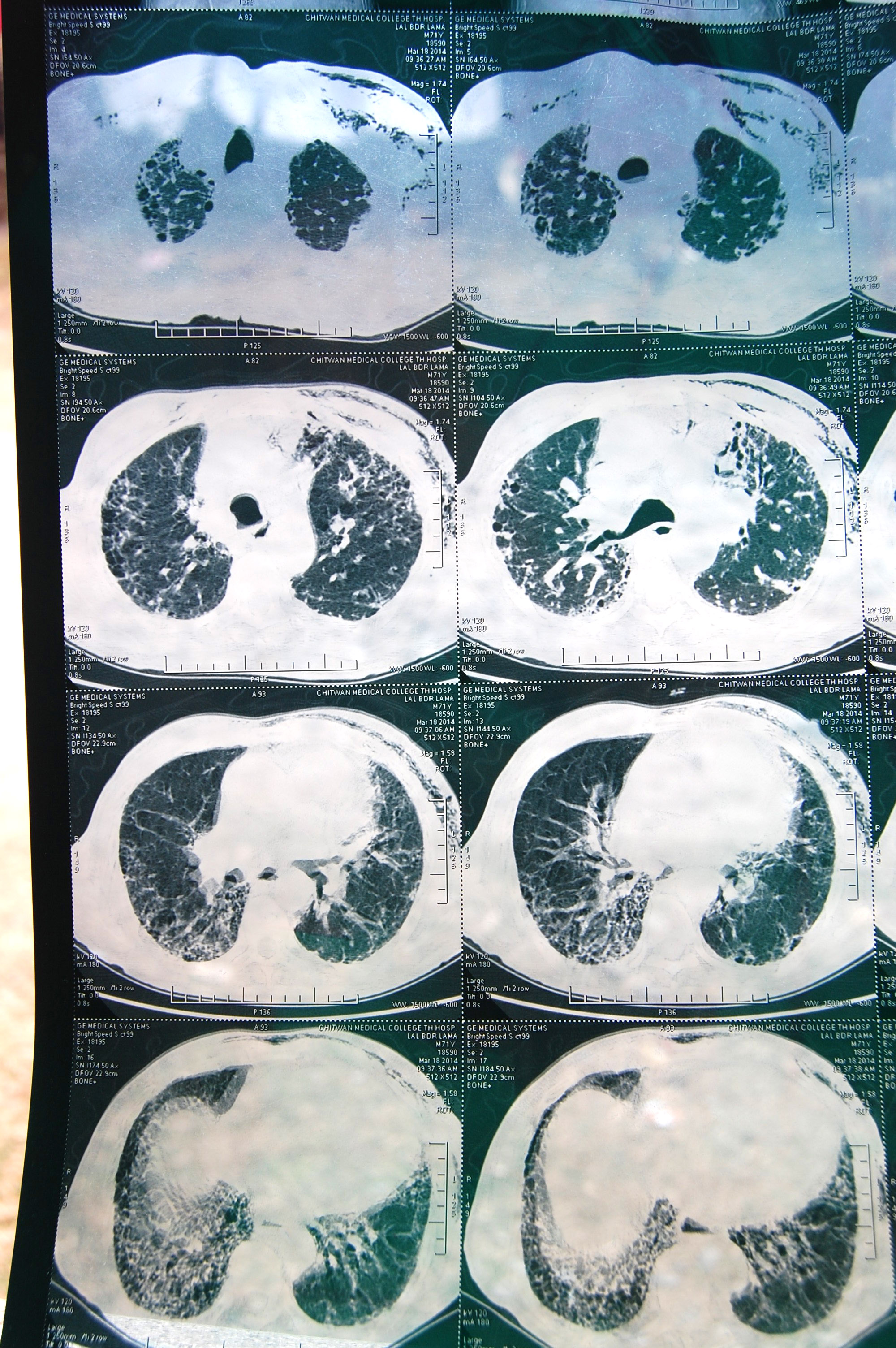

DX: Hospital records show that the patient was diagnosed with emphysema 10 months ago. X-rays show honeycomb cysts, and radiological conclusions communicate that a cyst in the “left middle lobe” burst, causing a pneumothorax.

This patient is a non-smoker and hasn’t had the occupational hazards that are usually associated with emphysema. It is likely that the lifelong use of a traditional Nepalese indoor cooking stove, with combustible biomass fuels, contributed to his disease state. In addition, x-rays show lower lobe thickening and concentration of bullae, which is a typical indicator of a genetic, alpha-1 antitripsin deficiency. This deficiency reduces the likelihood of cellular repair to lung tissue predisposing to emphysema, even with reduced exposure to inhalants.

TCM DX: Lung qi deficiency with obstruction by damp-phlegm and Kidney yang deficiency

PROGNOSIS: Patient’s condition worsens daily. It is evident that he is moving through the stages of grief, and acceptance of his death. Due to a PPS scale of 40, it is likely that he will die sometime in the next couple of months. An accurate BMI and FEV1 reading could help with a more accurate prediction of his lifespan, but the tools to measure this are not available to us at this time.

Initial Plan

Patient is recommended to go to the hospital, but he refused.

Plan for this patient focuses on improvement in his quality of life, palliation of symptoms associated with end-stage COPD, and support for patient and his caregivers around any other physical, mental-emotional or spiritual issues that may surface concerning his death process.

Typical treatment:

Monitoring of physical vital signs

Codeine, at a dose of 30g per evening, to provide minimal pain relief and reduction of cough so that the patient can sleep (This is purchased from the local pharmacy, where it is available to anyone.)

Cranial sacral therapy (CST) to release the occiput and tentorium cerebelli, to reduce anxiety and calm wheezing

Mild massage of the neck, shoulders and area between the shoulder blades

Education for patient and his family, including information about his disease, the cleanliness of his living area, danger of too much bed rest, etc.; Providing accountability for family members around his care

Emotional support around and witnessing the grief and death process; Discussion of the patient’s goals and desires for his final days

Drawing supplies and encouragement to engage in activities he finds enjoyable, including a small walk to the porch in the sunlight

Outcome

Outcome

During first contact, the respiratory emergency was stabilized and patient’s oxygen levels returned to normal ranges for his disease state. After that time, the patient showed relatively stable oxygen levels, less anxiety and was able to sleep through the night. He began sharing his life story, but was not yet able to discuss his death.

After 3 weeks, the patient presented with +4 pitting edema in his legs that prevented him from putting weight on his feet. He reported sharp chest pains. He became vocal about his death and stopped smiling and laughing as much.

At 4 weeks, the patient reported lowered anxiety and a feeling of increased relaxation. He asked for more practitioner visits, reporting feeling best on days when we came.

After nearly 30 patient contacts, the patient’s family reported a respiratory emergency with sharp chest pains. Upon arrival, pulse oximeter readings showed a blood oxygen level of 63% with a pulse of 34 bpm and respiration rate of 28. The patient could not maintain consciousness and at some point, could not recognize family members. Cultural traditions around death were already being performed by the family. He died during the night.

Discussion

In developed nations, the progression of COPD is delayed and the quality of life increased by using long-term oxygen therapy (small, portable tanks), and morphine to reduce the feelings of shortness of breath. Patients are recommended to follow a regular exercise and pulmonary rehabilitation program to maintain aerobic capacity and hence, maximum oxygen uptake.

A portable oxygen tank was not an option for this patient. His oxygen tank required 3 strong men to lift it into his room. The tubing to the tank allowed him 8 feet of movement from his bed. The costs of the tank were so high that the family often turned the tank off even though the patient would respond with blood oxygen levels in the low 70%. By the time of response to his respiratory emergency, he had been non-ambulatory, due to the tank, for over 15 days. With complete bed rest, elderly patients can lose up to 5-6% of their muscle mass each day and aerobic capacity decreases markedly1. Though it was recommended that the patient move each day, he reported that he was too weak to get out of bed.

This patient faced substantial impediments to obtaining morphine for pain control and relief of his shortness of breath. Had pain control been available for this patient, his quality of life would have been increased, and based on emerging studies, his lifespan may have been increased as well(2).

Conclusion

Conclusion

This patient and his family tried to get help from the local health post, a hospital in Kathmandu and a teaching hospital in Chitwan. They experienced an unfortunate misdiagnosis and multiple, failed attempts at a blood draw that left the patient’s arm completely bruised. During their final hospital visit, they were told not to come back, and were given medications for asthma and allergies. No healthcare provider explained the diagnosis to the patient, nor walked the patient and his family through the reality of his upcoming death. The doctor who prescribed the oxygen tank never spoke with the patient or his family about the risks associated with geriatric bed rest.

Though ARP is not an organization that commonly provides home care, and specifically, palliative home care, our team opted to continue providing such care in this patient’s case. The patient had no other options and our volunteers and interpreters were willing to spend the extra time, after a full day of clinical work, to perform vitals checks, and help educate the patient. Our organization is not often asked to provide end-of-life care and as such, we have not developed protocols for the management of these cases. This situation presented us with an opportunity to determine the resources that ARP can commit to such cases.

Our management of end-of-life care is dependent on the circumstances taking place outside of regular clinical hours. Are our volunteers and interpreters drained of energy from seeing a surplus of patients most days? In this case, we had numerous bus strikes that lowered our daily case loads, and I felt that I had enough energy to spend with the patient. The patient went through many stages of grief and as such, the nightly visits were emotionally charged requiring me to commit to a great deal of self-care, including morning and evening meditation, Taiji practice, writing and a lot of support from my team members. It was often hard to find an interpreter to volunteer to sit with a dying man when they faced the alternate choice of watching a movie or simply going to bed after dinner. This presented the possibility of resentment from the interpreters, which was something that I didn’t want to risk. I tried to rotate through the interpreters and to go either right before dinner, or shortly thereafter. This kept the task associated to a time that already held a social commitment, and it seemed to be less jarring for everyone.

As healthcare providers, it is hard to accept that no matter what knowledge we bring to the bed of a dying person, we will not find a way to “save” the patient and somehow magically restore their body. I encountered this difficulty in the first couple of weeks with Lal Lama. I worked all day to problem solve health issues that could be cured or managed. At night, I had to shift my intention so that I could listen to a patient’s story about his life and receive information about what his best death looked like, so that I could advocate for that if necessary. I had to tell the patient that there was nothing I could do to cure him, and that we were limited in the management of his pain. I felt myself unworthy of sitting with Lal and told myself that there must be a doctor nearby who could do this job better than I could. I finally came to realize that I was the best that Lal had, and in the end, I am so grateful that I embraced that and became the listener and friend that he needed. He taught me how to sit with the dying and how to die when the time comes for me.

As healthcare providers, it is hard to accept that no matter what knowledge we bring to the bed of a dying person, we will not find a way to “save” the patient and somehow magically restore their body. I encountered this difficulty in the first couple of weeks with Lal Lama. I worked all day to problem solve health issues that could be cured or managed. At night, I had to shift my intention so that I could listen to a patient’s story about his life and receive information about what his best death looked like, so that I could advocate for that if necessary. I had to tell the patient that there was nothing I could do to cure him, and that we were limited in the management of his pain. I felt myself unworthy of sitting with Lal and told myself that there must be a doctor nearby who could do this job better than I could. I finally came to realize that I was the best that Lal had, and in the end, I am so grateful that I embraced that and became the listener and friend that he needed. He taught me how to sit with the dying and how to die when the time comes for me.

1 Merck Manual

2 Lamas, Daniela and Rosenbaum, Lisa. Painful Inequities - Palliative Care in Developing Countries. New England Journal of Medicine. 366: 199-201. January 19, 2012.