News Blog

Latest News From Our Volunteers in Nepal

VOLUNTEER COMMUNITY CARE CLINICS IN NEPAL

Nepal remains one of the poorest countries in the world and has been plagued with political unrest and military conflict for the past decade. In 2015, a pair of major earthquakes devastated this small and fragile country.

Since 2008, the Acupuncture Relief Project has provided over 300,000 treatments to patients living in rural villages outside of Kathmandu Nepal. Our efforts include the treatment of patients living without access to modern medical care as well as people suffering from extreme poverty, substance abuse and social disfranchisement.

Common conditions include musculoskeletal pain, digestive pain, hypertension, diabetes, stroke rehabilitation, uterine prolapse, asthma, and recovery from tuberculosis treatment, typhoid fever, and surgery.

FEATURED CASE STUDIES

Rheumatoid Arthritis +

35-year-old female presents with multiple bilateral joint pain beginning 18 months previously and had received a diagnosis of…

Autism Spectrum Disorder +

20-year-old male patient presents with decreased mental capacity, which his mother states has been present since birth. He…

Spinal Trauma Sequelae with Osteoarthritis of Right Knee +

60-year-old female presents with spinal trauma sequela consisting of constant mid- to high grade pain and restricted flexion…

Chronic Vomiting +

80-year-old male presents with vomiting 20 minutes after each meal for 2 years. At the time of initial…

COMPASSION CONNECT : DOCUMENTARY SERIES

Episode 1

Rural Primary Care

In the aftermath of the 2015 Gorkha Earthquake, this episode explores the challenges of providing basic medical access for people living in rural areas.

Episode 2

Integrated Medicine

Acupuncture Relief Project tackles complicated medical cases through accurate assessment and the cooperation of both governmental and non-governmental agencies.

Episode 3

Working With The Government

Cooperation with the local government yields a unique opportunities to establish a new integrated medicine outpost in Bajra Barahi, Makawanpur, Nepal.

Episode 4

Case Management

Complicated medical cases require extraordinary effort. This episode follows 4-year-old Sushmita in her battle with tuberculosis.

Episode 5

Sober Recovery

Drug and alcohol abuse is a constant issue in both rural and urban areas of Nepal. Local customs and few treatment facilities prove difficult obstacles.

Episode 6

The Interpreters

Interpreters help make a critical connection between patients and practitioners. This episode explores the people that make our medicine possible and what it takes to do the job.

Episode 7

Future Doctors of Nepal

This episode looks at the people and the process of creating a new generation of Nepali rural health providers.

Compassion Connects

2012 Pilot Episode

In this 2011, documentary, Film-maker Tristan Stoch successfully illustrates many of the complexities of providing primary medical care in a third world environment.

From Our Blog

- Details

- By Rachel Hemblade

When I decided to go to Nepal to work on this project I knew that I would experience difficult situations that would challenge me in ways that I could never imagine. However, I wasn't quite so emotionally prepared as I had thought. It was our second day treating in the Bhimphedi clinic, and I was treating a young girl who looked no older than 3 or 4. She had been brought in earlier that morning with what looked to be an infected puncture wound behind her ear and she was distressed and crying. Perhaps frightened by the white coats and unfamiliar faces she would not let us near her to inspect the wound properly so she was dragged outside, which prompted all the patients outside to crowd around unnecessarily. This made the situation even more stressful. Despite the stress, noise and lack of communication, I could see that something was not right – her lymph nodes on her neck were visibly swollen and there was something unusual about the wound. I was feeling completely out of my depth but was expected to have this knowledge. I was relieved that the team leader was there who identified it as extra-pulmonary Tuberculosis (TB). Having experience in this environment and familiarity with such cases makes the difference in getting someone the right care.

I’m not sure what affected me more that day; the situation itself (that this child was clearly sick and had been for weeks, yet the parents didn't appear to be doing more to make sure she got better) or the fact that they had gone to see various healthcare professionals and still none of them had recognized this as TB. With each day that passes and as we get used to living in this culture, I realize that it is not that people don't love and care about their children – it’s that in some situations they don't know how to care for them or that there’s nothing else they can do. The lack of basic healthcare education means that a lot of children are really sick and nothing can be done about it.

What we have also come to realize and what makes me feel more disheartened is that even if and when they get to the hospitals or health posts, we cannot guarantee or expect that whoever sees them will be anymore qualified or knowledgeable than ourselves. This sense of frustration that I have found myself feeling over the past weeks occupies my thoughts most of the time and makes me wonder what can be done to help with the situation.

This is why I am so grateful to be here: To be working alongside such caring professionals who are collectively developing trust in this community so people can have the confidence to come to us with these concerns. The Acupuncture Relief Project clinic is perfectly placed to spot these serious health issues and drive positive change in the community through proper action, education and awareness. -- Rachel Hemblade

- Details

- By Andrew Schlabach

I would like to thank everyone who so kindly offered support and donations to help us respond to this terrible event.

One month after what is now known as the Gorkha Earthquake, our organizational attentions are returning to our primary mission. The 7.8 magnitude earthquake that occurred on April 25th, 2015 killed more than 8,800 people in Nepal and was followed by days of heavy aftershocks, some as strong as 7.3Mw.

In the first few days following the initial quake, we scrambled to make contact with our friends, staff and villages. Our foreign volunteers and volunteers of other associated organizations were escorted to their respective embassies who assisted in evacuating them to their countries of origin. We learned that no one associated with our project had been injured though several of our staff members homes had sustained damage. The villages of Bhimphedi, Kogate and Ipa, where we operate our clinic projects, sustained significant damage but only minor injuries.

After making an initial assessment, Acupuncture Relief Project and our local host organization, Good Health Nepal, started looking at emergency response plans. We made contact with USAID, Mercy Corps, Chokgyur Lingpa Foundation, several embassy officials and other organizations. We were strongly encouraged not to try to place a team in Nepal until receiving permission from governmental, military and police organizations. Instead we collected our Nepali staff and opened an office in Kathmandu. Lead by our ARP coordinator and Director of Good Health Nepal, Tsering Sherpa and his wife Sera Sherpa, this office staffed a 24-hour hotline where organizations could access our interpreting staff to support medical teams being sent to the field.

Interpreters were sent to Sindupalchowk and Nuwakot to support doctors and nurses in these remote villages. Other Good Health Nepal volunteers surveyed villages and distributed dust masks and tarpolines. More importantly, the office served to coordinate the efforts of several organizations in the distribution of medical and emergency supplies. They were able to provide government agencies critical data about the needs of the villages where we operate. We were even able to provide some funding and support to a group that was sheltering animals that had been traumatized and displaced during the earthquake.

I am so very proud of our staff for there efforts over the last few weeks. I think it is testament to the work we have done over the past several years that we had a trained group of young men and women ready and able to organize and provide practical, effective skills in the aid of their own communities. What we were able to accomplish with a few thousand dollars was truly amazing.

At this point, with the monsoon season starting, things are returning to some form of normal for Nepali’s. There are still many people living in temporary shelters and tent cities however schools and businesses are reopening and crops are being planted. Most people are turning their attentions to rebuilding their lives. We too are looking on to what happens next.

As of June 1st, we are closing our “emergency office” and sending our staff back to their home villages to help their families. Our first order of business is to assess the damage to our clinic building in Bajra Barahi and to prepare for a clinic team to resume our operations when the monsoon ends (early September). Tsering is traveling to Makawanpur to check on our clinic and also assure the District Health Office and our communities that we are eager to return to our work there. We know that the buildings and infrastructure may take many years to repair but we intend to address the trauma and emotional scars that fear and loss inflict as soon as possible. Our challenges will also include many health concerns due to damage of sanitation systems and healthcare facilities in our region. Currently the World Health Organization is projecting a major outbreak of Typhoid and other infectious diseases over the summer months.

Personally I am looking forward to being back in Nepal in September to reestablish our momentum in the training of healthcare providers in Makawanpur. The longer that we operate in Nepal, the more I see that the future depends upon inspiring and enabling Nepal’s young people to take responsibility for their community’s social welfare. Of course, this is always what we think in times of crisis. What we really need to think about is how rural areas of Nepal need access to compassionate, competent healthcare and social workers all of the time. -- Andrew

Andrew Schlabach, MAcOM EAMP

Director, Acupuncture Relief Project

Bhimphedi, Makawanpur, Nepal

Donate to the Earthquake Relief Fund

For current news please Like Us on Facebook

- Details

- By Andrew Schlabach

For as much as we glorify the medical profession it is actually a much simpler job than it seems. Don’t get me wrong, being a medical provider requires years of training and experience. In the developed world, medical providers are held to extraordinarily high standards. They should be as they are compensated very well for their responsibilities and we need their skills. My observation has less to do with expertise and more about attitude.

“How can I help you?”

This simple question should summarize our relationship with our patients by placing us in a role of service to our patients. Unfortunately, all too often, the question is presented more in the light of “What is the problem?”. This slight difference in language changes our role and places patients in our service rather than us being in theirs.

Nothing could be more clear in the developing world than the disparity between those who have money and those who don’t. People with money receive good access to medical care and are generally regarded with respect when visiting a clinic or hospital. Those who don’t have money, well… they are ignored. In Nepal, I have witnessed on many occasions, doctors who never made eye contact with their patients. I have seen them talk on their cell phone while they rifle though the patient’s records and summarily write prescriptions, sending their patient on their way without so much as two words exchanged. For the patient, this impersonal visit is often at the cost of their family’s land and livelihood. Again, there are many doctors who do very fine work and I’m not denying that hospitals, doctors, labs and technology do not cost real money —of course they do. As professionals, we need to make a living the same as everyone. The question is more one of, how do we serve our patients equally? How do we see each human being as a unique and valuable part of our community, equally entitled to our attention? For that, our profit driven system seems to fail us.

This year, I worked with one of our volunteer practitioners trying to manage a very persistent outer ear infection in a young Tamang girl. After several weeks of treatment with saline and vinegar flushes, topical herbs, oral and topical antibiotics, and topical anti-fungal agents, she still presented with a deep abscess just above the tympanic membrane. We referred her for a tuberculosis test to rule out a rare form of skin TB. It came back negative. Here is where it gets difficult for us, because we run up against the family’s ability to pay for other more extraordinary care. We appealed to the District Health Office for assistance and they requested that we obtain a referral from the local health post. After consulting with the doctor at the heath post, she agreed that the girl needed surgery to clean and close the abscess. However, she declined to write us the referral because “She [the patient] can’t afford the surgery, so what is the point.”

Now, dear reader, please don’t worry. These road blocks do not stop us and we generally find a way to help our patients. It is also not my intention to single out this one doctor because this is an attitude that pervades the entire health system. I would like to say it pervades the system “in Nepal” but I feel the problem is more far-reaching.

In my mind I ask, how can this be an acceptable response? How can it make sense to allow a persistent infection progress into permanent hearing loss or worse? How can that possibly serve the community?

In Nepal, the answer is that the doctor is not a part of the same community. He or she is separated by a gulf of education, opportunity and other socio-economic advantages. Doctors lose sight of the purpose of their service.

The other issue is that healthcare providers often don’t look beyond their own conclusions for treatment. When we have been trained to think an abscess equals surgery, it is hard to back away from that edge in order to think about other possible solutions or approaches. To remedy this, we need to take a more holistic approach to patient care. On an individual level, we talk about holism in the context of the patient, where we don’t just look at the disease process but rather we look at the whole person and how the disease is effecting their overall wellbeing. We need to extend this thinking to how we look at our overall system of delivering care. Instead of looking at medicine as individual modalities or treatment specialties, we need to go back to pondering how we can best alleviate a patient’s suffering. Often times it has more to do with providing information and education than it has to do with intervention, but it is impossible to arrive at this conclusion if we immediately jump to treatment.

Look at the fact that many research studies [1][2][3] show that the strength of the patient/practitioner relationship has a direct correlation to the patient’s medical outcome and it should be obvious that treating each and every individual with kindness and respect should go without saying. Yet, in my experience, this relationship seems to be lacking. This is especially true in the rural areas of Nepal where our patients are mostly illiterate and lack the education to ask even the most basic questions about their health. The doctor (I use this term loosely because usually the patient is seeing a health assistant and not a doctor) asks “what is wrong with you?” and then prescribes them a list of medications. Of course the patient has no idea what the medications do, they just believe that they will be cured. When they are not cured, they do not know what to do next. We have found that by just taking the time to clean an infected wound while explaining how to use simple soap, water and exposure to direct sunlight not only kills the infection and heals the wound but also prevents future infections. This simple practice injects new information into the community and effectively inoculates many would-be patients through dissemination. This is so much less-expensive and safer than the common practice of treating superficial infections with antibiotics.

At our clinics, we have the advantage of seeing our patients many times and we start to know them and their families. We laugh and joke with our patients (something unheard of in Nepal) and we start to understand their unique needs. We earn their trust and that trust allows us to help them in ways that transcend medical intervention. I am certain that our volunteers get tired of me telling them that a patient has the right to know their diagnosis. They should know the details of the prescribed plan (or medications) and what the expected outcome is. It is so simple. However, throughout Nepal’s medical system (and probably our own), patients lack this basic information. If they were armed with this information, they could make their own choices regarding their care. They could agree to be served by us, they could seek other advice, or they could do nothing. It would be in their hands.

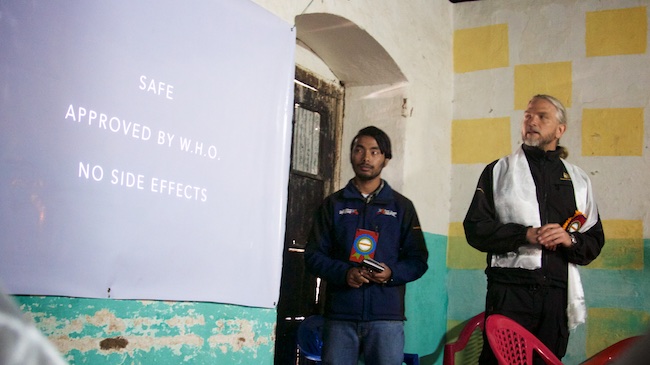

This year we hosted our first ever formal community and press meeting. We invited our patients, community leaders, district health officials and members of the local and national press to hear what we have accomplished in Nepal and our ideas on transforming the rural care system. It was sort of a grandiose plan but it was very well attended and received. The District Health Chief spoke very highly of our service in Makawanpur and pledged his support in looking at a more holistic model of providing care. He introduced us to a new area in Makawanpur called Bajra Barahi which is regarded as a model health post in Nepal. Their development committee listened to our presentation with interest but also a heathy amount of skepticism. They had experienced several disappointments from other NGO’s who promised large benefits but delivered shoddy medicine with many poor outcomes. They were also very concerned about the sustainability of our efforts.

My response was simple. “We either earn the trust of your community and show you that we can be effective or else it doesn't matter if we are sustainable or not. We offer a simple, safe and effective addition to your health system in which we work side-by-side in partnership with your existing staff and facilities. If we show you that our system is effective, it is easy to adopt and sustain without us. We will show you how and you will have a model which you can share with every district of Nepal.”

They were satisfied with that answer and in the weeks that followed many doors opened for us. Baja Barahi’s development committee offered to give us a small clinic building and land within the existing health post compound. This new partnership with the district government has been the opportunity I have been looking for since beginning this project in 2008. It is our first opportunity to not only care for patients, but to start working on transforming the rural care system as a whole. In other words, now we have the opportunity to put-up or shut-up.

This is quite the mandate and to meet this challenge we truly have to address our sustainability. Since beginning in Nepal, we have recognized that it is not practical or cost-effective to sustain our project with foreign practitioners. Unfortunately the problem of training and properly certifying acupuncturists has been a major obstacle. A system of accreditation and licensure does not exist and we envision training a type of health-care worker that does not yet exist. Ideally this hybrid “Rural Care” provider would be trained in both basic allopathic medicine (same as the existing health assistant) as well as acupuncture, bodywork and medicinal herbs. They would support other doctors, heath assistants and health post staff but also provide holistic health advice, simple and effective treatment and be an advocate for integrated patient care. In order to be useful in strengthening Nepal’s rural health system, these new providers would need to be able to work independently in some very remote regions.

Our solution materialized in the form of a small acupuncture school in Kathmandu that was struggling to get started. Founded by a Japanese NGO and staffed by a few Nepali acupuncturists that were trained in China, the Rural Health and Education Service Center (RHESC) was able to acquire certification through Nepal’s vocational education system in 2013. That is a start but falls short of certifying the kind of provider we are looking for. This year we were able to form an alliance with the RHESC and I was honored to be given a position on their Board of Directors. My task is to write a curriculum that will be accepted by Nepal’s Health Professions Council, allowing them to offer a bachelors degree in Acupuncture and Rural Health Care.

I had the privilege of teaching a five-day seminar on the shoulder joint to the RHESC’s second year students and was impressed by their appetite for opportunity and education. Our challenge is to inspire them to work in rural areas where they are needed most. Starting in September 2015, we will be hosting 12 RHESC students as clinical interns. This mentorship program will allow students real-world field experience under our guidance and offer the district government the opportunity to see the potential of future employment of RHESC graduates. We have encouraged several of our current interpreters to compete for government scholarships available to students in rural areas for enrollment in the RHESC program. This will be the key to sustaining our clinics in areas like Kogate which is too small for us to sustain a permanent clinic.

These are all just the first few wobbly steps in the right direction and while all of these developments are exciting prospects, I try to root myself in my own experience. From there I see that when it comes to patient care, sometimes I can have a major impact on a person’s life. Other times I struggle to offer even the slightest relief no matter how hard I try. Either way I hope that I never fail at making my patients feel cared for. With this simple idea, I believe we can make a ripple in a much bigger pond.

Author: Andrew Schlabach, MAcOM EAMP

Director, Acupuncture Relief Project

Bhimphedi, Makawanpur, Nepal

Our Mission

Acupuncture Relief Project, Inc. is a volunteer-based, 501(c)3 non-profit organization (Tax ID: 26-3335265). Our mission is to provide free medical support to those affected by poverty, conflict or disaster while offering an educationally meaningful experience to influence the professional development and personal growth of compassionate medical practitioners.